Sign up for a new account.

And get access to

The latest T1D content

Research that matters

Our daily questions

Sign up by entering your info below.

Reset Your Password

Don't worry.

We will email you instructions to reset your

password.

“The prevalence of depression is three times higher in people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) than in the general population.” – Tapash Roy and Cathy E. Lloyd, in Journal of Affective Disorders

“Adults with T1D who also have untreated depression face worse health outcomes, lose more time from work, have increased healthcare costs, and have higher HbA1cs than individuals without depression.” – JDRF

“It’s really challenging to have a disease where you have to work at it 24/7 to stay alive when your mind is telling you to give up.” – Syd, Illinois

The research is clear: There is a definite link between type 1 diabetes (T1D) and depression, and these comorbidities represent a significant threat to the health and wellbeing of many people living with T1D.

What the statistics can’t show us, though, are the actual experiences that come with simultaneously managing T1D and depression. While quantitative data is invaluable, it can’t recreate the thousands of individual stories it comprises. It can’t reveal the personal side of either disorder, let alone their combined effect.

As a person with T1D and a mental health ally, I am drawn to these stories—and I also have a lot of questions about them. Or, rather, I have many versions of the same question, which is this: How?

How does a person count carbs, calculate insulin doses, change pump sites, or do any of the other countless tasks of diabetes self-management if they are depressed? How do they take steps to prevent future complications when the future feels inconceivable? In short, how can someone survive a physical illness while in the throes of a serious mental one?

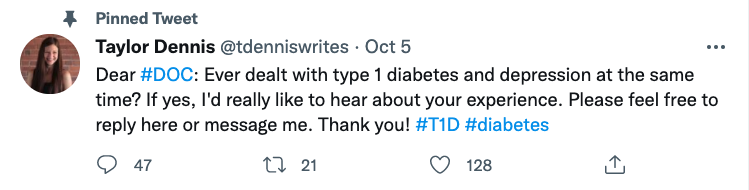

To truly understand the experience of living with T1D and depression, I needed to go straight to the source. So, I turned to Twitter:

The responses soon began rolling in. I was overwhelmed, in the best way possible, by the number of people who were willing to share their stories.

I spoke to people of all ages and backgrounds from across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. I heard from some who had been living with T1D for decades and others who had been much more recently diagnosed.

I had set out to understand the how of T1D and depression. In the course of discovering some the many answers to that question, I also had the privilege of uncovering the who.

The Who, the How, and Beyond

I ended up speaking to dozens of people who had experienced both T1D and depression. Although the stories I heard were just as diverse as the people who shared them, I noticed a few common themes: the relationship between depression and glucose variability, the role of technology, and the prevalence of other comorbidities.

For many people, depression was associated with greater glucose variability, including higher A1Cs and less time spent in range. “On my non-depressed days, I can achieve, like, 95% time-in-range,” said Zack from Toronto. “On bad days, it can be as low as 30%.” Another respondent, Heather from Michigan, explained, “[When I’m depressed], I forget to bolus for a snack or a meal until my blood sugar goes high and my Dexcom alarms. Or I get a headache or my vision goes blurry from the high blood sugar.”

And then there was Jason from North Carolina, who put a fine point on the underlying emotions that can lead to increased glucose variability: “You know, no one wants to eat healthy or go to the gym when deep down they hate themselves.”

These responses were in line with research that has demonstrated a link between depression and long-term complications of diabetes associated with glucose variability. Interestingly, though, a few people actually said they’d had the opposite experience. “Sometimes when I was very depressed, I’d have a hard time eating,” explained Deanna from San Francisco. “And then, honestly, my blood sugar was even better, which was a bad thing to see as a positive correlation.”

Jason from Washington had a similar story. “If anything, my A1C was actually lower during periods of depression, because I’d either be trying to be perfectionistic and controlling it out of frustration, or just sleeping so much with a DIY system on that I’d end up with long periods with great blood sugars as a result.”

Like Jason, many of the people I spoke to relied on technology to manage their diabetes, especially when dealing with depression. They relied on their pumps, continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), and especially closed-loop systems. “When I got the CGM, it changed things and I was controlling better,” said Sarah from Washington. “I basically just let the technology keep me alive.”

Still, technology isn’t a cure-all. While most of the people I spoke to said they relied heavily on their diabetes technology, some also struggled to keep up with the maintenance of their tech while depressed—for example, by leaving pump sites in for longer than recommended.

Technology also has its limitations when it comes to impacting behavior; while an alarming CGM certainly makes it tougher to ignore an out-of-range blood sugar, even this is not always enough. “In the mindset of depression and anxiety, I don’t take the action needed to get back to normal levels with my blood sugars,” explained Mandie from Texas.

Complications and comorbidities were also a common theme—especially mental health comorbidities, including anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and borderline personality disorder (BPD). According to research, such comorbidities are very common among all people diagnosed with a mental illness.

One comorbidity stood out: Several people, including Sarah from Arizona, mentioned that they also have diabulimia. This unofficial, T1D-specific eating disorder involves intentionally restricting insulin to control weight. “I think [the diabulimia] is related to depression, as my sadness would manifest with trying to control my weight and eating,” said Sarah.

Diabulimia and other disordered eating behaviors have been linked to diabetes distress, which Sarah also touched upon: “I’m sure I would have depression even without diabetes, but it’s been a complicating factor,” she said. “The amount of daily decisions, stress, bad doctors, financial drain, and lack of support or understanding from many people all compound the issue.”

The Why Behind This Article

When I began to write this article, I wanted to understand how it was possible to manage both T1D and depression. Having lived with the former condition and watched several of my loved ones battle the latter, I could hardly fathom coping with both simultaneously.

Even now, after speaking to dozens of people about their experiences, I know that I will never quite comprehend the challenges that come with this unique set of comorbidities. But I do have a much better idea than I did before, and for that I am immensely grateful. With pages upon pages of notes to work from, I could have written much more from the responses I received—and one day I probably will.

To everyone who answered my tweet: Thank you. Thank you for your willingness to share your experiences with a complete stranger on the internet. Thank you for agreeing to lend your words to this article. And thank you, truly, for your honesty and openness, without which we could never begin to break down the thick stigma that still exists around both diabetes and mental illness.

Articles like this one have an important role to play when it comes to confronting that stigma. But of course, this type of content needs more than just willing contributors—it also needs readers. And so, to everyone who took the time to read this post: Thank you, too. Thank you for caring, learning, and getting to know the real people behind the data.

If you or a loved one with T1D are struggling with depression, the following resources may be helpful:

- ADA’s Mental Health Provider Directory: https://professional.diabetes.org/mhp_listing

- Find a local support group through your T1D healthcare provider, or attend a local/virtual event with Beyond Type 1, JDRF, College Diabetes Network, or another T1D organization near you.

- Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741-741 (Available 24/7)