Sign up for a new account.

And get access to

The latest T1D content

Research that matters

Our daily questions

Sign up by entering your info below.

Reset Your Password

Don't worry.

We will email you instructions to reset your

password.

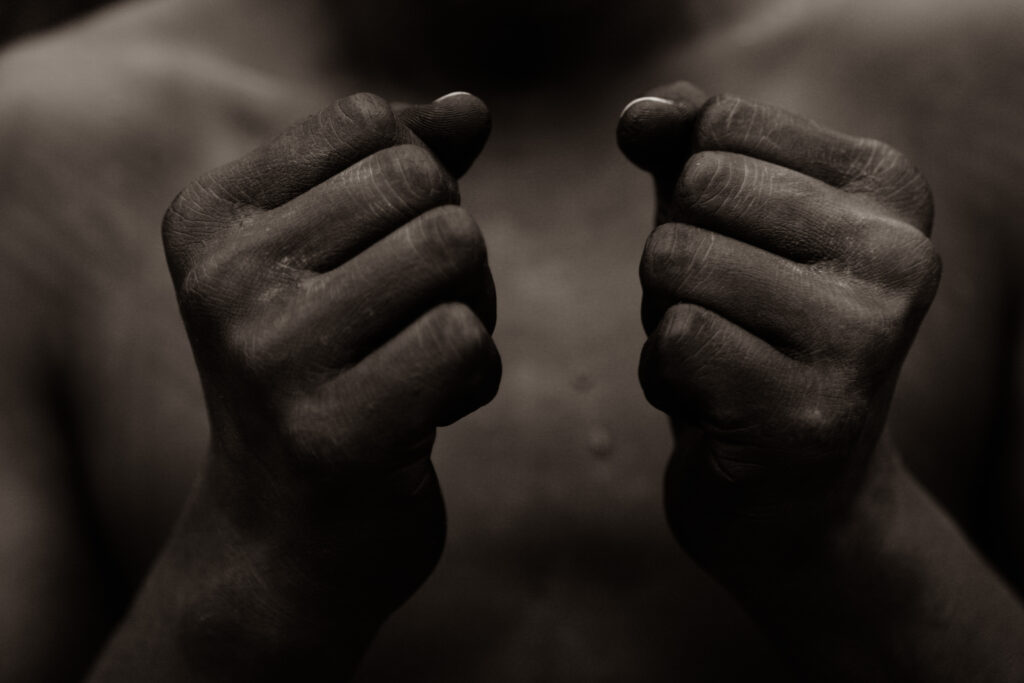

Frankly, what we know about the healthcare provided to people of color with type 1 diabetes (T1D) is heartbreaking and infuriating.

Today, we celebrate Juneteenth — the commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States — but this day should also look at life today and in the future for Black people. While equality has come a long way, our research reminds us how much further we need to go.

In diabetes, we know that Black people are not receiving the same healthcare as non-Black patients. In fact, we can give you the nitty gritty details that paint this picture quite clearly thanks to research from the T1D Exchange Health Equity Advancement Lab (HEAL) program.

In diabetes, we know that Black people are not receiving the same healthcare as non-Black patients. In fact, we can give you the nitty gritty details that paint this picture quite clearly thanks to research from the T1D Exchange Health Equity Advancement Lab (HEAL) program.

Our research says people of color with diabetes are:

- Less likely to be prescribed a continuous glucose monitor (CGM)

- Less likely to be prescribed an insulin pump

- Less likely to receive education regarding newer diabetes technology

- Less likely to have access to CGM and insulin pump technology

- Less likely to be prescribed newer types of insulin and glucagon medications

- More likely to develop complications including neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy

- More likely to be frequently hospitalized for severe hypoglycemia

- More likely to be frequently hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

Is your race preventing your doctor from prescribing a CGM?

Unfortunately, the answer is yes. Your skin. Your name. Your clothing. Your voice. These beautiful details that makeup who you are can trigger a conscious or unconscious prejudice in your healthcare provider, changing the way they manage your diabetes care.

Our research finds that many healthcare providers have an “implicit bias” towards patients of a certain race or ethnicity that they are likely not even aware of — and it’s preventing that provider from prescribing things like continuous glucose monitors and insulin pumps.

Research led by Dr. Nestoras Mathioudakis, an endocrinologist and Associate Professor of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine determined the following difference in technology use based on race and ethnicity.

In a study with about 1,200 participants:

- Only 7.9% of Black patients use a CGM

-

- vs. 30.3% of non-Black patients use a CGM

- Only 18.7% of Black patients use an insulin pump

-

- vs. 49.6% of non-Black patients use an insulin pump

Mathioudakis also points out that a large majority of hospitalized patients with diabetes don’t have this critical technology — highlighting the impact it has on your daily safety managing T1D.

We are working to change this

This won’t change overnight, but we believe we can make a difference — and we work daily on this endeavor. We’ve developed a custom “bias training” program to help providers identify, prevent, and change prejudice in healthcare provided to people of color with diabetes. The results are clear:

More than 200 healthcare providers received our custom “bias training”.

The impact on 880 patients of those providers:

- 21%increase in CGM prescriptions for all races/ethnicities

- 32% increase in prescriptions for Black people

How YOU can help change healthcare for Black people with diabetes

We need your voice. We need your participation. We need people of color to participate in impactful diabetes research by joining the T1D Exchange Registry. When you join the Registry, you’re simply creating your own personalized portal that invites you to participate in a huge variety of research throughout the year — mostly from the comfort of your own couch!

We value your voice. We need your voice. We want to make a difference and we need your help.