Sign up for a new account.

And get access to

The latest T1D content

Research that matters

Our daily questions

Sign up by entering your info below.

Reset Your Password

Don't worry.

We will email you instructions to reset your

password.

Our mission at the T1D Exchange is to improve the lives of people living with type 1 diabetes (T1D). A large part of how we accomplish this mission is through research.

At the T1D Exchange, our Outcomes Research team collaborates with leaders in the T1D space and with other experts at the T1D Exchange to design studies to understand the preferences, experiences, and quality of life of people living with T1D in our Registry and Online Community.

If you are a part of the Registry, you’ve likely seen study opportunities pop up on your dashboard. You may have even participated in some of these studies! And you may have wondered: what happens after you participate?

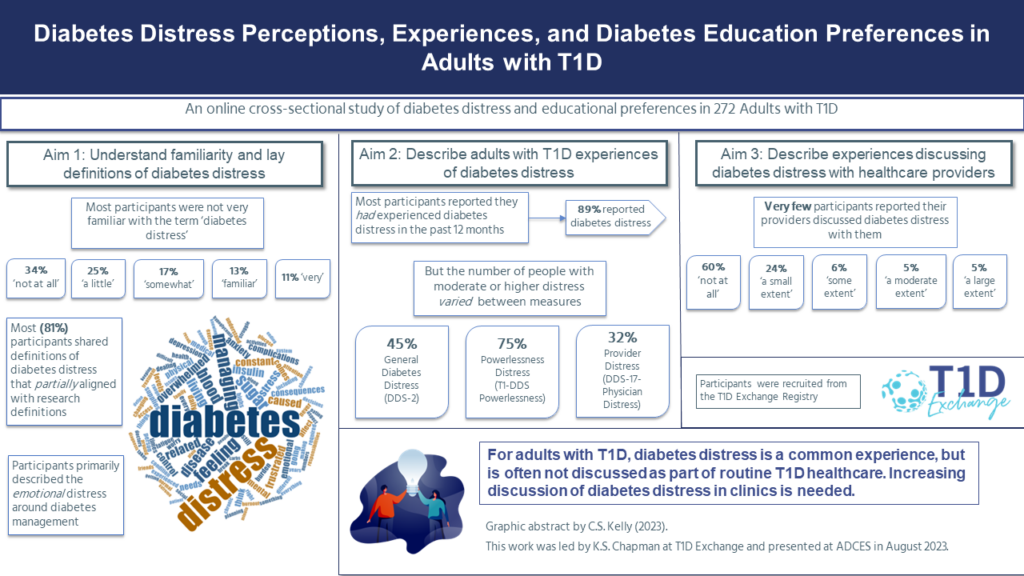

Here, we’ll highlight the results of one of our recent studies on diabetes distress and preferences for education in the T1D Exchange Registry: Diabetes Distress Perceptions, Experiences, and Diabetes Education Preferences in Adults with T1D. These findings were presented at ADCES 2023’s annual conference.

What is diabetes distress?

Even if you’re not familiar with the phrase, you probably already have some idea of what diabetes distress is: it’s the negative emotions — or ‘distress’ — felt because of living with T1D.

We know managing T1D is a 24 hour a day / 7 days a week job. Each day with T1D means hundreds of more decisions to make just around management. But people with T1D must also balance management with everything else in their lives — work or school, relationships — along with daily management and not-so-daily management (such as having to visit a health care provider more often, interact with diabetes supply companies, and other regular aspects of T1D care). All of this can be stressful. This stress can lead to a person feeling overwhelmed, at least at some points in their lives. At those times, many people with T1D experience will experience diabetes distress.

An important caveat about diabetes distress is that it is not the same thing as depression or anxiety. It is related to mental health, in that if you are experiencing a lot of negative emotions related to diabetes, it can evolve into other conditions like diabetes burnout or even depression. But, to properly manage diabetes distress, you need a diabetes specialist or a professional trained in chronic illness management to help.

What does research say about diabetes distress?

There are many research studies about diabetes distress (such as this one from Drs. Lawrence Fisher and William Polonsky and this review of a quarter of a century’s worth of studies in diabetes distress). The American Diabetes Association also highlights that diabetes distress is an important clinical outcome for diabetes management and recommends providers should consider and screen for diabetes distress when possible as part of their 2023 Standards of Medical Care.

But what is unclear from research is how well providers and researchers are communicating to adults with T1D about diabetes distress.

So, the Outcomes Research Team designed a study, led by Katherine Chapman, to understand more about perceptions of diabetes distress to explore how much overlap there is between lay definitions and research-based definitions of diabetes distress. We also explored to what extent adults with T1D felt their providers had discussed diabetes distress with them and their preferences for learning more.

Study Overview: Diabetes distress and education preferences in adults with T1D

We recruited and enrolled adults with T1D from the T1D Exchange Registry to understand three questions:

- How do people define ‘diabetes distress’ in their own words?

- Using different measures, how can we describe adults’ experiences with diabetes distress?

- How much do adults report their providers have discussed diabetes distress with them as part of their T1D care?

Summary of Results

In the graphic abstract below, you’ll see an overview of our findings.

In our sample, most people stated they were not very familiar with the term ‘diabetes distress’. However, when asked to define the term in their own words, most participants were able to hit on many of the aspects of what makes diabetes distress distressing: the felt emotional experience around managing T1D.

In our sample, most people stated they were not very familiar with the term ‘diabetes distress’. However, when asked to define the term in their own words, most participants were able to hit on many of the aspects of what makes diabetes distress distressing: the felt emotional experience around managing T1D.

Most participants reported feeling diabetes distress at some point in the past year, but when measuring diabetes distress through standard (or ‘validated’) measures, we found that the number of people who would be classified as having moderate diabetes distress varied a lot. The measure that was most specific to T1D, the T1-DDS: Powerlessness subscale, suggested that most people were experiencing moderate distress. However, more general measures (like the DDS-2) or measures less about the felt experience of distress (distress around health care providers from the DDS-17) showed fewer people classed as having moderate distress.

Finally, most of the participants in our sample stated that their providers have not discussed diabetes distress with them at all (60%) or only to a “small extent” (24%).

Conclusions and Implications: The ‘So What?’ Summary

The takeaway from this study shows there is more work to do for researchers and providers to get on the same page about diabetes distress with adults with T1D.

Most adults in our study were not familiar with the term for diabetes distress, but many had experienced it within the past year – across a variety of measures. In our sample, most of our participants were already meeting the American Diabetes Association’s recommended guidelines for an HbA1c level under 7.0%. But, doing well with T1D management as measured by blood glucose outcomes like HbA1c doesn’t mean managing T1D is easy. At least at some point in the year prior to the study, most adults in our sample (89%) reported they had experienced diabetes distress.

Despite the high reports of distress, most adults in our sample stated that their healthcare team had discussed diabetes distress with them to a ‘small extent’ or had not discussed it with them at all. Moreover, as discussed in the full presentation, many adults would prefer to receive information about diabetes distress from their healthcare team.

Our findings highlight the need for more care around the emotional impact of having T1D as part of regular diabetes care in a way that resonates with the people they treat.

Caitlin Kelly

Related Stories

1 Comment

T1D Exchange Outcomes Research Spotlight: Diabetes Distress & Education Preferences in Adults with T1D Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Managing obtaining the timely delivery of pump and CGM supplies as well as experiencing quality control issues with manufacturers is increasingly frustrating and contributing to DD. As a patient and T1D survivor of 50 years, I have never been more frustrated and frankly disappointed by “successful “ companies growing indifference to poor customer service and a shift from patient centric to profit centric business practices.