Sign up for a new account.

And get access to

The latest T1D content

Research that matters

Our daily questions

Sign up by entering your info below.

Reset Your Password

Don't worry.

We will email you instructions to reset your

password.

Author’s Note: A special thank-you to my mom, Jackie Dennis, for her contributions to this article—and for so much more.

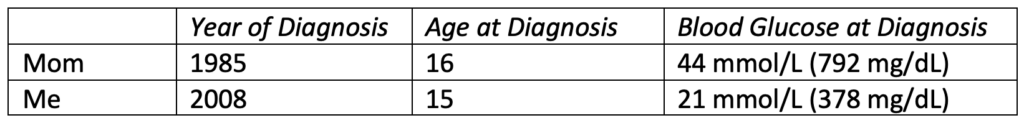

I have been living with type 1 diabetes (T1D) since the age of 15, but the condition has been a familiar part of life for as long as I can remember. The sight of needles, the clicking sound of a lancing device, the smell of insulin . . . much like the taste of Kool-Aid, these sensations are woven into my childhood memories. This is because decades before I developed T1D, my mom received the same diagnosis.

According to research, because my mother was younger than 25 when she had my older sister and me, there was a 1 in 25 chance of each of us developing the condition. My brother was born when Mom was 26, which means there was only a 1 in 100 chance for him. These odds would have doubled if Mom herself had developed T1D before the age of 11.

According to research, because my mother was younger than 25 when she had my older sister and me, there was a 1 in 25 chance of each of us developing the condition. My brother was born when Mom was 26, which means there was only a 1 in 100 chance for him. These odds would have doubled if Mom herself had developed T1D before the age of 11.

Of Mom’s three children, I am currently the only one with T1D. At this point, it is unlikely that my siblings will ever develop the condition. Shortly after my diagnosis, both were screened for participation in a study for family members of people with T1D. Neither qualified for the study, because the screening determined they do not carry the genes that account for roughly 50% of the genetic risk for T1D.

Although I would prefer for us to both have fully-functional pancreases, I am grateful to have a T1D comrade in Mom. Not just someone who can sympathize, but someone who knows exactly what I am going through. Considering the naturally isolating nature of T1D, this companionship means a lot.

I recently asked Mom if she would like to share details about her diagnosis and early treatment. She was happy to tell her story, which I have recounted below in her words. When her experience is placed back-to-back with my own, a strong theme emerges: Progress.

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

To best demonstrate the differences in our experiences, I’ve broken Mom’s account into three categories: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. The sections below are written in her words, with my own commentary included below each section.

Diagnosis

Mom’s Story

“When I think about the time before my diagnosis, what I remember most is feeling exhausted. Although I managed to go to school every day, it was a struggle to get up in the morning, and I went back to bed as soon as I got home. My mother woke me up for dinner every day. Even though I felt like I was starving, I could hardly eat. Shortly after, I would head to my room and go back to sleep.

Finally, my mom decided I needed to go to the doctor. In addition to the exhaustion, I had lost over 20 pounds in a short amount of time. I didn’t think that was a big deal. After all, I was a teenaged girl. Being thin was cool!

Not long after that doctor’s visit, my mom met me in the hallway one morning as I was getting ready for school. She said the doctor had phoned the night before. I had diabetes, and I would need to go to the hospital—today.

I shrugged my shoulders and continued getting ready for school. My poor mom followed me around anxiously, then reluctantly agreed to pick me up from school once she heard back from the doctor. I remember getting on the bus and telling a friend that “apparently” I had diabetes. I knew nothing about T1D at the time, except that two of my adult cousins had it, and they were often unwell.

I didn’t stay at school for long that day. I got the call during first period to leave, and then the next chapter of my life started.

I was hospitalized for one week. During that time, I started taking insulin and learning about carbohydrate exchanges and sliding scales. At 16 years old, the only information that really stuck was that I was not allowed to drink or smoke, I had to follow a regimented eating schedule and take daily injections, I would likely not be able to have children . . . and all of this was all forever.

I spent the second week after diagnosis in a different hospital where I participated in a clinical trial for cyclosporine* as a treatment for sustained remission in recent-onset patients. I participated in the study for 18 months as an outpatient. There is no way for me to know whether I received the drug or the placebo; however, I did experience increased hair growth, which is a known side effect of the drug. Unfortunately, I did not experience sustained remission.

Before writing this, I spoke to my mom about her recollection of events. She told me that on the evening I was admitted to the hospital with a blood sugar of 44 mmol/L (792 mg/dL), the doctor had said that without insulin, I might not make it through the night.”

(*) It is impossible to know for sure if this was the study Mom participated in. However, the linked study is consistent with the timeline, location, and details she provided.

My Commentary

Like Mom, I experienced weight loss and extreme fatigue at the time of my diagnosis. Because our family was familiar with the signs of T1D, my symptoms were observed much more quickly. I was not sick enough to be hospitalized and was able to start taking insulin at home under Mom’s supervision and guidance.

Diet at Diagnosis

Mom’s Story

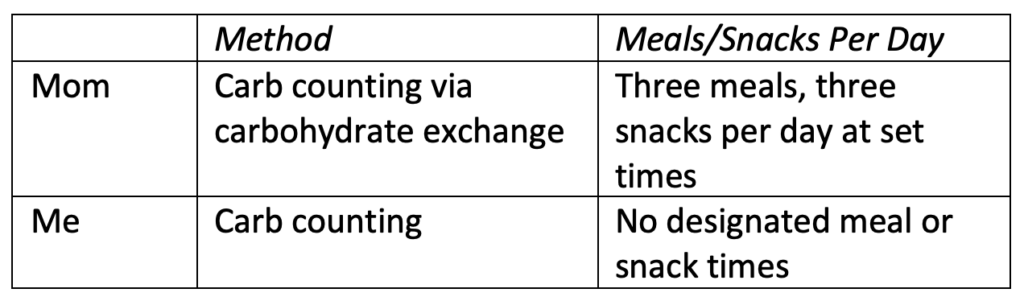

“When I was discharged from the hospital after diagnosis, I was prescribed a diet of three meals and three snacks per day. My insulin doses were also prescribed.

I was taught carb-counting using the carbohydrate exchange method. Certain foods belonged to certain groups, and the approximate volume of a particular food would count as a serving or “unit” of carbs. I was then prescribed a certain number of macronutrient units for each meal. For example, breakfast consisted of 2 units of carbs, 1 protein, and 1 fat (e.g., 2 pieces of toast and peanut butter). There were also “free” foods that didn’t need to be counted, such as cucumbers and eggs. I had a chart that I could use to plan my food and meet my requirements for the day.”

My Commentary

Unlike Mom, I was not prescribed a diet. I did not have set meal times or macronutrient requirements. This is because, unlike Mom, I was able to adjust my rapid-acting insulin with each meal. Rapid-acting analog insulin did not hit the market until 1996.

I was also taught to dose for the net carbs (carbs minus fibre) in food. Today, I also take protein and fat into account, as I’ve found that both have a major impact on how my body breaks down carbs.

Insulin Routine at Diagnosis

Mom’s Story

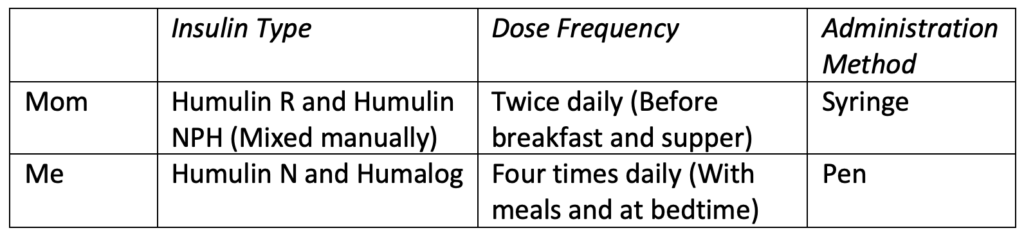

“Along with my required macronutrients for each meal, my insulin doses were also prescribed. I took insulin before breakfast and before dinner, and once I took my dose, I was committed to eating the set number of carbs until the next dose.

This was a problem. Who decides at 7:00 a.m. what they want for lunch? What if your plans change? Got invited to go out for pizza at 3:00 p.m.? Not going to work. Dinner is going to be at 7:00 p.m. tonight? Sorry, I’ll have to eat at 5:00 and then watch you eat later. This was very challenging, particularly as a teenager.

Physically taking insulin was also a hassle. I had to draw it from vials and mix it twice a day—once before breakfast, and again before dinner. Travelling anywhere meant keeping insulin cool, and it also meant trying to find somewhere discreet to break out my supplies. I also needed a surface to put everything on and a way to keep things clean. The introduction of insulin pens was a huge relief for me.

My regimen left no room for spontaneity, so my prescribed plan for every day looked the same. I would love to say this worked, but it was always a challenge.

When I got pregnant in 1989, I was immediately put on four injections per day: one before each meal and one at bedtime. Blood glucose control was critical for ensuring the best environment to grow a healthy baby. This new regimen was amazing and afforded me more flexibility. Being pregnant also made me much more compliant. I had the best glucose control I’d had since diagnosis, and I felt amazing throughout the entire pregnancy.”

My Commentary

After my diagnosis, I was placed on the same insulin regimen my mom was currently on: one shot of intermediate-acting insulin at dinner, and one shot of rapid-acting insulin with breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Today, I continue to take rapid-acting insulin with meals and as-needed for corrections. However, my intermediate-acting insulin was replaced first by long-acting, and then again by ultralong-acting. Mom began using a pump in 2020 and has never looked back.

Blood Glucose and Ketone Measuring at Diagnosis

Mom’s Story

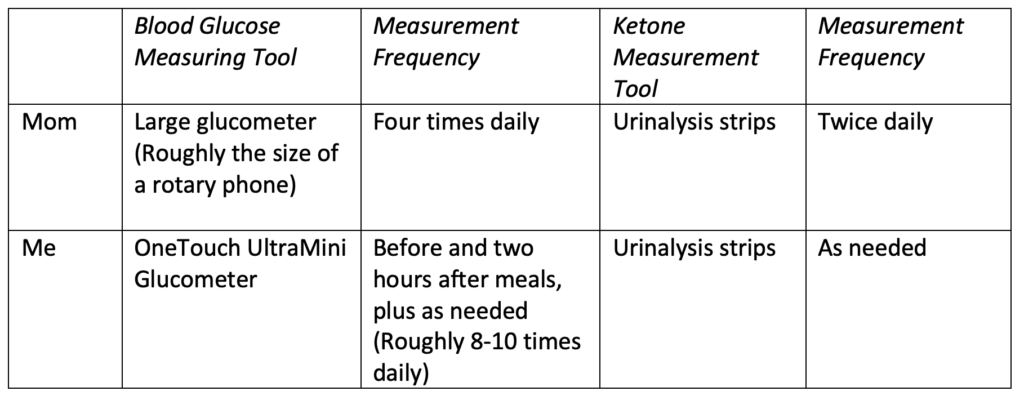

“I only checked my blood sugar four times a day, and I had no idea what was happening between those four checks. My glucometer was roughly the size of a rotary phone, and it took two minutes to deliver the result each time.”

My Commentary

Unlike Mom, I was encouraged to check my blood sugar two hours after every meal. However, I was also able to check it any time I felt it might be too low or too high. Because my parents had excellent insurance coverage, I was able to use unlimited test strips without worrying about the cost.

Since I had regular insight into my blood glucose levels, I was not prescribed ketone-testing strips or instructed to test for ketones regularly. Instead, I was told to purchase and use these strips if I ever experienced potential symptoms of ketoacidosis. To this day, I have never tested for ketones.

Prognosis

Mom’s Story

“When I was diagnosed, I felt angry, bitter, and hopeless. There was nothing positive coming from any adult at that time. Instead, I was being given a long list of things to avoid and an even longer list of ways I had to take care of myself.

I was also very lonely. I had no one to talk to about diabetes. I was not offered counselling. The nurses were all very flip at the hospital—doing their jobs and nothing more. At this and other times in my life, T1D has been very isolating, especially because I’ve known few other people with the condition.

My prognosis was also fairly negative at diagnosis. Things like neuropathy, retinopathy, and kidney damage/failure were very common for young people with T1D in the 1980s. But changes in diabetes management were happening quickly after my diagnosis, and with each new change the prognosis improved.

Throughout my life, I have always been incredibly fortunate to have extended benefits that cover most of the medical costs related to diabetes. I believe this has been crucial to helping me stay healthy for the past 37 years.

One thing my doctors strongly discouraged was having children, but that was something I was not giving up. After having my first child, I suffered one miscarriage. My OB assured me that this had nothing to do with my T1D, and that the miscarriage was not my fault. His words were incredibly comforting. Today, I am proud to say I have three healthy, amazing adult children.

Managing diabetes is completely different now than it was when I was diagnosed. You seldom hear the term “diabetic diet” anymore, for one thing. The tech has also advanced so much. Though I fought it for a while, now I fully embrace my pump and continuous glucose monitor (CGM), which have afforded me freedoms I never imagined I could have again.

Diabetes is still a full-time job. There are no vacation days. That is a lot some days. But I’m healthy and expect to live to be an old lady. That was not always a thought that I entertained.”

My Commentary

Perhaps the most profound difference between my experience and Mom’s can be seen in our prognoses. For me, although being diagnosed with T1D was scary, I did not need anyone to tell me I could live a full life with the condition. After all, I’d been watching Mom do just that for 15 years. I continued to see nothing but possibilities.

When she was diagnosed in the 1980s, Mom received the opposite message. She lived with T1D before insulin analogs, CGMs, the conclusion of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), and so many other advances in medication, technology, and knowledge. As a result, she was told that the rest of her life would be defined not by possibility, but by limitation.

Hearing Mom’s story, one thing becomes clear: The strong example she set as a capable, independent, healthy person with T1D was a testament to her personal resilience . . . or, as those who know her best might call it, her stubbornness.

Today, I am very grateful that Mom will almost certainly live to be an old lady—stubbornness and all.