Sign up for a new account.

And get access to

The latest T1D content

Research that matters

Our daily questions

Sign up by entering your info below.

Reset Your Password

Don't worry.

We will email you instructions to reset your

password.

Growing up in Cayce, South Carolina, sports defined W. Guyton Hornsby’s childhood. A standout running back on the football field and a track athlete, Guy (as he’s known) was captain of his eighth-grade team, and at 15, earned a spot on high-school varsity.

Growing up in Cayce, South Carolina, sports defined W. Guyton Hornsby’s childhood. A standout running back on the football field and a track athlete, Guy (as he’s known) was captain of his eighth-grade team, and at 15, earned a spot on high-school varsity.

That same year — 1968 — he experienced sudden, dramatic weight loss, dropping from 152 to 107 pounds. One Sunday that spring, when home from church, he remembers eating a large lunch of fried chicken followed by two whole apple pies by himself to the great consternation of his family. “I had all the symptoms,” he recalled, “the weight loss, peeing all of the time, just starving to death.”

The doctor told him he had type 1 diabetes (T1D). With a blood glucose of 812 mg/dL, Guy was told he’d be okay once he was taking insulin, adding that he would likely live to age 40. “I was just glad that they knew what it was,” he said, remembering the relief he felt at the news. “I was so sick, tired, and worn down. When you’re that young, you don’t think about how long you’re going to live.”

In the hospital for two weeks, the endocrinologist recommended he begin exercising. He ran up and down the eight flights of hospital stairs for an hour, followed by 1,000 push-ups and 1,000 sit-ups — every day. His goal was to get back on the field for the next football season.

But the following year, the coach only allowed him to punt, unsure how to manage a player with diabetes. Guy insisted on training with the other running backs, out-practicing them, and in his senior year finally convinced his coach to let him try to carry the ball during a quarter-long exhibition match. He never looked back, scoring two touchdowns and rushing for 150 yards in that one quarter.

He was strong and fast, and that year ended up leading the state in rushing, gaining an average of 9.7 yards per carry, Guy said. Also, during his senior year, he excelled in track, setting school records in the 100-yard and 220-yard dashes, as well as the long jump. That combination of determination, talent, and perseverance to overcome odds would shape every stage of his life.

Now 73, Dr. Guy Hornsby has lived with T1D for more than five decades. He’s seen the field of diabetes care revolutionized by new technology, advances in medication, and a new generation of groundbreaking scientific research — some of which he has helped shape as a diabetes and exercise researcher and policy advisor.

A scholar-athlete’s turning point

After high school, Guy attended the University of South Carolina on a track scholarship, where he lived a dual life as an elite athlete with T1D, managing his training sessions without the aid of modern tools like a continuous glucose monitor. He mostly kept on top of his diabetes care. The scariest episode, he said, was the day after a tough practice when he became hypoglycemic and walked out of his dorm naked and disoriented, eating his roommate’s birthday cake in front of a surprised crowd at a baseball game. The sugar from the cake saved him.

After high school, Guy attended the University of South Carolina on a track scholarship, where he lived a dual life as an elite athlete with T1D, managing his training sessions without the aid of modern tools like a continuous glucose monitor. He mostly kept on top of his diabetes care. The scariest episode, he said, was the day after a tough practice when he became hypoglycemic and walked out of his dorm naked and disoriented, eating his roommate’s birthday cake in front of a surprised crowd at a baseball game. The sugar from the cake saved him.

“Well,” he said, matter-of-factly, “when you’re hypoglycemic, you know you have to eat.” He said it was fortunate his roommate had just had a birthday, and his girlfriend had brought him a chocolate cake, which was sitting there on the counter. He laughed, “The cake brought me back.”

After college, Guy shifted from competitive sports to scholarship, majoring in sports education. He earned a master’s degree and began coaching, but after a few years, he felt he wanted more. The motivation came, as was typical, out of his competitive drive.

“I was working in a running shoe store to pay for college,” he recalled. “And two of my friends came in to see me.” They told him they were working on their PhDs in exercise physiology at Louisiana State University (LSU), and Guy mused that maybe he should follow them.

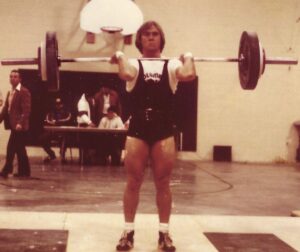

They teased him, saying, “Well, we don’t think you’re smart enough.” That was all the motivation he needed. He called the graduate coordinator at LSU’s physical education program and got a spot. At the university, he began coaching weightlifting, a sport in which he was also competing. Once he was doing graduate work, he said, it made sense to gravitate toward diabetes research.

He earned his PhD in exercise science in 1983.

A career shaping diabetes science

After he graduated, Guy became a postdoctoral fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina. There, he joined the research team for the landmark Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), which transformed modern diabetes care by demonstrating decisively that intensive management of glucose levels prevented or delayed complications from diabetes.

He said that working on the trial team was among his proudest moments, taking part in research that would become foundational for all subsequent work in the field.

“I believe that I was the only exercise physiologist who was working on the DCCT study at the time,” he recalled, which meant he was the contact for all participants who were athletes. “We had a tennis player and a golfer, and when they would become hypoglycemic, we would work out ways for them to manage their glucose and keep up with their events.”

He later served for six years as program chair of the American Diabetes Association’s Council on Exercise. He helped author its influential position statement on exercise and diabetes, drafted in 1990 and since updated. The report established the core value of exercise as part of taking care of one’s health with diabetes, a summation in many ways of Guy’s personal lifelong dedication to physical activity as a cornerstone of a life full of health and vigor.

In the report, his team indicated that exercise should be a high priority for those with type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, “for people with type 1 diabetes,” the report continued, “the emphasis must be on adjusting the therapeutic regimen to allow safe participation in all forms of physical activity consistent with an individual’s desires and goals. Ultimately, everyone with diabetes should have the opportunity to benefit from the many valuable effects of physical activity.”

Looking back, his transition from competitive athlete to coach, then to diabetes researcher and policy maker seems fluid — a natural evolution that carried as many similarities as differences. His competitive spirit fueled his academic ambitions as much as it did on the field. After mastering his own diabetes management, he was inspired to help others gain that same confidence and feel free from limitations.

He taught at West Virginia University School of Medicine for the next 32 years as a professor of exercise physiology, publishing two books, 15 book chapters, and over 50 articles on diabetes and exercise. He retired in 2021 as a professor emeritus, with much of his research focusing on the benefits of strength training for people with T2D.

His research found that exercise does more than build muscle — it helps maintain stable glucose levels, supports a healthy weight, and has a strong impact on mental health. Adding, “We found that exercise was an important component in helping people with depression.”

Staying active with T1D

After five decades living with T1D, Guy still prefers multiple daily injections paired with a Dexcom 7 continuous glucose monitor. “My A1C is hardly ever over 6.5,” he said. “Why would I change to something which might mess it up? Why change what works?” said Guy, who has never had an interest in trying an insulin pump.

After five decades living with T1D, Guy still prefers multiple daily injections paired with a Dexcom 7 continuous glucose monitor. “My A1C is hardly ever over 6.5,” he said. “Why would I change to something which might mess it up? Why change what works?” said Guy, who has never had an interest in trying an insulin pump.

A fractured hip, osteoporosis, and a persistent frozen shoulder have slowed him in recent years, but he continues to be active. Movement had been a constant in his life. He walks every day and aims to overcome his injuries so that he can compete again.

“I wish I could get back to competing in weightlifting,” he said, wistfully, but with the good-natured determination that has been his hallmark. “I really want to do that. My hip and my broken femur have healed enough to do that, but I’m having trouble with my frozen shoulder. I just can’t hold a bar over my head.”

Music, travel, and a new stage of life

He spends his time now writing music and traveling the world with his wife, Dr. Jo Ann Hornsby, a retired physician whom he first met through research work, and spending time with his two sons, one of whom followed his footsteps, playing football and running track in school, followed by earning a PhD in exercise physiology and coaching weightlifting. Neither of his sons has T1D.

Away from academia, Guy’s life is full of creativity. A lifelong musician, he plays guitar, banjo, and harmonica, although Dupuytren’s contracture, which limits the movement of his fingers, makes playing harder now. Instead, he has turned to writing songs, collaborating with friends — and now with AI voices — to bring them to life.

“I don’t play as well as I used to,” he said, sitting in his music room below a signed group portrait of The Monkees, one of his favorite bands from the 1960s. “What I’ve gotten into now is writing songs. So, I’m a songwriter. Well, I’ve written three songs, which probably doesn’t qualify me as being a songwriter.”

One of his songs — his best so far, he says — “On the Avenues,” begins: “I remember my childhood home in Casey, South Carolina, with mom and dad and my sister Susan. Life was peaceful and happy on the avenues.”

He and his wife now use their time for travel, including, for the past nine years, an annual Flower Power Cruise with their favorite bands from the 1960s. “Most of them are in their 80s now,” Guy laughs.

Lessons from a life of strength, determination, and T1D

Starting from the time he was a teenager, wanting to return to playing football after his diabetes diagnosis, to becoming a standout athlete, a coach and mentor, and then a scientist whose work has influenced the course of diabetes care, Guy has competed and excelled in multiple arenas.

He recognizes that he’s been fortunate. His diabetes has never slowed him down and has pointed the way for accomplishments during his distinguished career as a mentor, teacher, and researcher.

Guy cautions: He didn’t do it alone. He had family, mentors, and teachers the whole way. His most important advice to others with T1D is to find trusted individuals to learn from and rely on. “The most important thing,” he said, “is to work closely with a certified diabetes educator. That’s where you will get the best knowledge about what to do.”